Rostam's Seven Trials: Hybrid Work Sketch & Essay

- A'liya Spinner

- Jun 4, 2024

- 12 min read

Introduction: the rite of passage

The male rite of passage— from boyhood to manhood both physically and socially— is shared almost universally among mythologies, often presented as a series of challenges that must be consecutively overcome. Perhaps the most well known example is the twelve labors of Heracles, through which he redeems himself to his father and society. The Maya Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque must also undergo a series of trials in the Underworld throughout adolescence; the Celtic king Pwyll is granted his crown only after successfully completing a year of rulership and tribulations in the fairy realm; Sigurd the Dragon Slayer is described as being a youth when he kills Fáfnir, setting him on the heroic path. In each instance, the task(s) are the turning point in the mythos surrounding our male champions. (Interestingly, both Sigurd and Rostam also bathe in dragon’s blood.)

One of the most famous rites of passage in the Shahnameh are the seven labors undergone by the hero Rostam. Rostam is a descendant of both Zahhak— one of the most supernaturally evil villains in the Shahnameh— and Zal, a renowned hero and Simurgh-blessed king. As Rostam enters his teenage years, the newly-annointed king of Iran, Kavus, is goaded by a disguised Eblis into starting a war against the demons of Mazandaran. Against the advice of Zal and other wise men, Kavus leads the Persians against the Div and is promptly captured. Young Rostam and his supernaturally-strong horse Rakhsh are then sent to rescue Kay Kavus, undergoing unique trials along the way.

These seven labors all carry individual meaning, but the same idea of a ritual transformation to manhood can be broadly applied. Mahmoud Omidsalar wrote about this extensively in his article, Rostam's Seven Trials and the Logic of Epic Narrative in the Shāhnāma. However, his focus revolved almost exclusively on the White Demon and the Oedipal symbolism of defeating an effigy of his own father. While I certainly agree with his analysis in this regard, I am expanding Rostam’s rite of passage to include all seven of his trials, culminating in his encounter with the White Demon. Through this hybrid exploration of art and artist statements, I conceptualize the trials faced by Rostam as reflective of the qualities expected of adult, male heroes in the world of the Shahnameh. Each piece engages with both the text and a little of the artistic tradition surrounding historical depictions of the episode.

A note on the depiction of Rostam: Rostam will always be wearing his iconic tiger skin cloak, but will not have the “head” until his combat with the White Demon, as I think the parallel of those visages is striking (it is also not uncommon for Rostam to not be wearing the head in depictions of his trials.) Additionally, as a mode of conveying his youth, I have kept his facial hair reduced compared to historical depictions. References for his outfit, poses, and trials are taken directly from the rich tradition of manuscript illuminations and modern art.

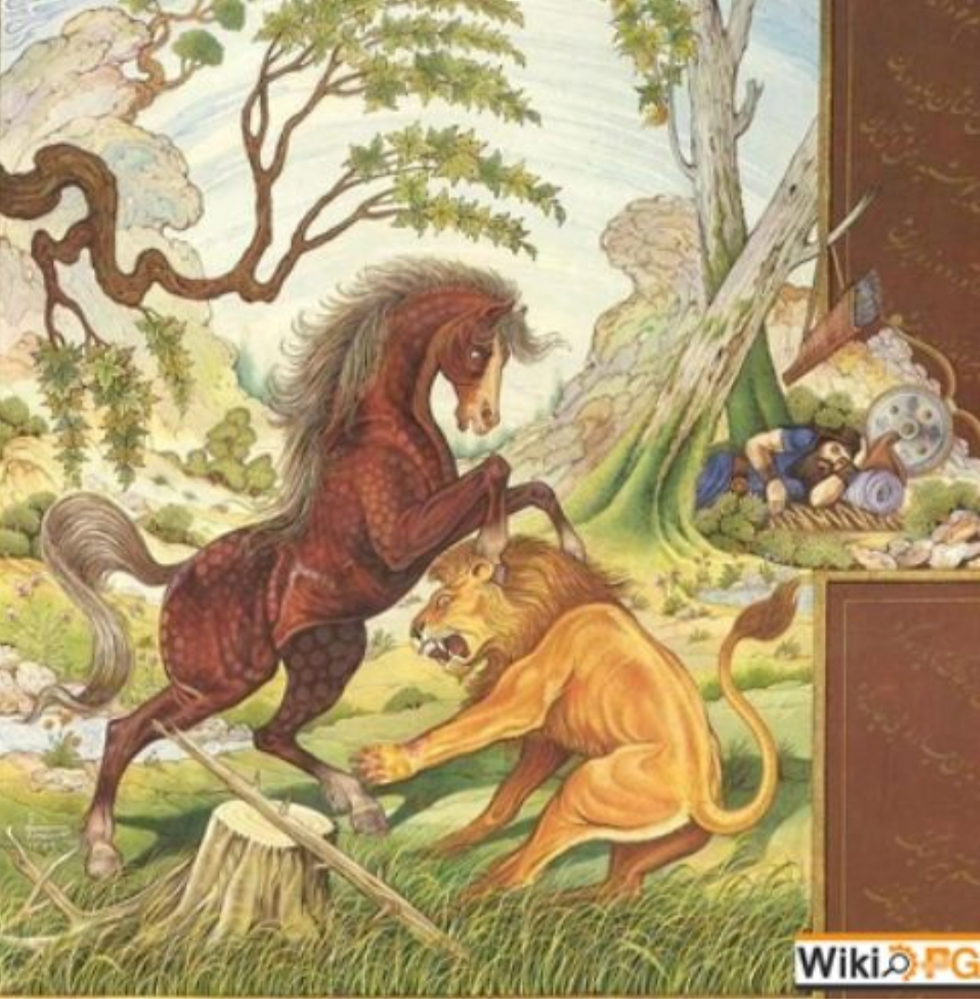

Rakhsh vs the lion - Awakening Virility

The first of Rostam’s trials is one in which he is entirely asleep; his horse, Rakhsh, kills a lion that is stalking him as he rests. Rakhsh is described as having “sharp teeth” and being fearsome as a dragon, as well as supernaturally strong and large (being able to carry Rostam when all other horses crumpled under his weight.) Certainly, Rakhsh is a bit more than “just a horse”, similar to how Rostam is a bit more than “just a man”. Their bond is nearly instantaneous and persists unwaveringly for the entirety of Rostam’s six-hundred year life until the pair die (and are then entombed) together.

Across cultures, stallions are representative of male virility, aggression, and independence. Within the realm of the Shahnameh, we are shown that horses are also tied to a man’s honor: heroes boast of being skilled horsemen, and Forud humiliates his enemies by shooting their horses beneath them, forcing them to walk back to camp (pg. 292). Rostam separates the young Rakhsh from his mother, transforming the foal into a ferocious stallion concurrently with Rostam’s transition into manhood. In many ways, Rakhsh is an extension and representation of Rostam’s masculinity. They come into maturity together and live inseparably. Rakhsh is wild, too. He proves that he (or, perhaps, they) are more powerful than nature’s most fearsome beast: the ravaging lion. Rostam then chastises the horse; in a sense, he is learning to curb his own inner wildness throughout this transitory stage in his life.

In this piece, I have depicted the battle between Rakhsh and the lion. Rakhsh is depicted with his characteristic “sharp teeth” and leopard spots. The spotting is a trait that many artists throughout history have given to Rakhsh, perhaps to emphasize his uniqueness among horses, and his seemingly predatory nature (Appendix C).

2. Finding the Ram - Trust in God

Rostam, like all good people of the Shahnameh, is shown to be extremely devout throughout his life, praising and giving thanks to God before and after many of his battles. This faith is tested and rewarded during his second labor, wherein he must cross an inhospitable desert. When he and Rakhsh both collapse from heat and thirst, Rostam does not curse his fate— instead, he looks to the heavens and tells God that “if my pain is pleasing to you, my treasure is amassed in another world. I travel in the hopes that God will have mercy on King Kavus…” (pg. 153) Rostam acknowledges that his mission— indeed, his life— is beholden only to the will and pleasure of God. His faith is rewarded by the appearance of a healthy ram, which Rostam follows to a spring of water. He calls down blessings on the animal, and exclaims, “Whoever turns away from the one God has no wisdom in him; when difficulties hem us in, he is our only source of help.” (pg. 153). As part of his transition to heroic manhood, Rostam is affirming that neither his strength nor trickery is as vital to his survival as the favor of God.

In this piece, I have chosen to depict Rakhsh and Rostam as mere silhouettes against the backdrop of the desert, small and unimportant. Instead, the ram is large both in frame and in stature, representing the animal’s inspiring vitality and the great power of God that outshines even the greatest hero; the circle behind the ram’s head could be interpreted as a halo or the scorching desert sun. This dichotomy between a desperate Rostam and the holy ram was especially inspired by modern Iranian artist Hamid Rahmanian’s print, “The Second Trial: Rostam in the Desert from Shahnameh: The Epic of the Persian Kings” (Appendix A).

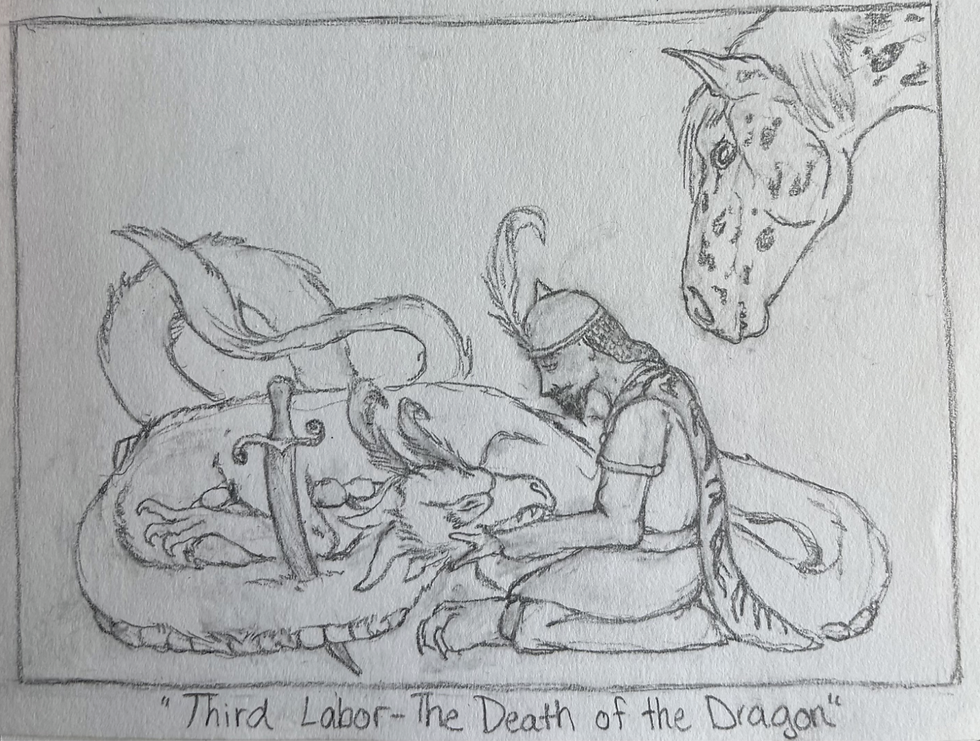

3. Slaying the Dragon - Destroying Internal Evil

To me, the most incredible of Rostam’s trials— and perhaps one of the most powerful moments in the Shahnameh— is his battle with the dragon, and its aftermath.

Rostam himself is something of a mythical creature; his father’s mother was the Simurgh, while his mother’s father descended from Zahhak, who can be considered both demon and dragon. At times, it seems as if Rostam is a dragon or that he rides a dragon; he is the only person ever shown to speak with a dragon, as he and his enemy goad one another in the darkness of the mountain pass, and he flies the standard of a dragon as he ages (pg. 200). In a rare moment of genuine peril for our hero, Rostam is almost overcome in the battle against the serpent; he is saved only by the intervention of Rakhsh. Rostam “stares in horror” (pg. 155) as the dragon’s blood and poisons gush over the desert— such horror at one’s own actions is extremely rare in Shahnameh, even when kin-slaying or razing forts and kingdoms. He then wades into the viscera and washes himself in it, praying to God for mercy and strength.

In my interpretation of his labors as a transitory state for Rostam, this is the moment when he permanently slays a piece of himself. Like Mehrab, Afrasyab, and Khosrow, Rostam is partially descended from an evil bloodline. And, like them, he must either defeat or succumb to this inherited darkness. Rostam is a dragon, powerful enough to lay waste to armies and kingdoms but determined to use this strength for the good of Iran. Yet the blood of Zahhak is also strong and fierce, preying on him when he is vulnerable and susceptible to being led astray; it is a battle he almost does not win, more deadly than any external combat. And while it is certainly a victory to destroy this monster, it is a loss, too. Rostam watches in fear and despair as a part of himself is slain. He washes himself solemnly in the blood; perhaps he is reabsorbing a hint of its power, now able to be controlled and wielded for the good of Iran, much like Rostam himself will become a weapon for the Kayanian kings. There is a stillness in this scene; the chaotic, explosive Rostam pauses, mourning and honoring the sacrifice.

Understandably, many artists (both historically and in the modern tradition) choose to illustrate the epic combat between Rostam and the dragon. However, I’ve depicted a quieter scene: the moment of contemplation that follows the death of the serpent. Rostam kneels and cradles its head in his hands. Their plumed crests mirror one another, and the dragon coils around Rostam such that it is difficult to truly delineate between the two. Rakhsh— the unwavering strength of Iranian manhood, and Rostam’s savior during this trial— looks on.

The horrible dragon is defeated— and what was the cost?

4. Slaying the Witch - Discipline, resisting temptation

The artistic tradition surrounding Rostam’s fourth trial— the slaying of a sorceress— is overwhelmingly violent, depicting the moment Rostam skewers or severs the disguised witch-woman. This is certainly the climax of the story and a victory for our hero, but it is not, in my opinion, the ultimate lesson to be learned from the labor. Rostam is no stranger to violence, and his vanquishing a “withered old woman” (pg. 156) is hardly a hard-fought triumph. Once she has been revealed as a trickster Div, there is no doubt that Rostam will prevail. The labor, therefore, is what precedes this moment of violence.

Rostam stumbles upon an idyllic scene in the desert, with sparkling streams of water, roasted chickens and delicacies, wine, golden goblets, and musical instruments. He immediately gives in to his desire and sits to feast. He drinks, eats, and plays the lyre, even singing a song about his own great deeds and his annoyance at having to rescue Iranian kings (which is quite the unbecoming thing for a hero to say.) When he is approached by the disguised sorceress, he is not suspicious of her— he gives thanks to God that along with this mysterious meal he has encountered a beautiful serving girl. The true adversary of this story is Rostam’s own impulsiveness and greed. In the demon-ruled land of Mazandaran, Rostam should certainly have known better than to expect that partaking uninvited in a desert feast would have no negative consequences, and he should have been wary of a stranger approaching him, no matter how beautiful. As a trickster himself, it’s all the more embarrassing that Rostam was almost fooled by the Div until the name of God forced her to reveal herself. The lesson he learns from this labor is not necessarily to slay sorceresses, but to reject temptations. Discipline is required of an adult warrior, and Rostam must overcome both sexual and gluttonous desires— as well as laziness and bitterness— during his journey.

For this piece, I have chosen to depict the sorceress with her disguise lowered and her breasts prominent. She is a Div of Mazandaran (something that is inconsistent in historical artworks, as artists struggled to “pinpoint” her appearance), as I believe that “witch” denotes a magic-practicing woman, rather than a separate species. Rostam sits at a grand table of food and drink, so distracted by the feast and his desire that he is oblivious to the obvious danger posed by the stranger.

5. Capturing Olad - Mercy and Honor

The Div Olad is one of the most curious characters in the war against Mazandaran; unlike the warrior Divs that Rostam cuts down in droves, Olad is a civilian landowner who seems much more human than demon. In fact, Olad’s servant is introduced saying to Rostam, “You Ahriman, why did you let your horse wander in the wheat, spoiling the property of someone who’s never done you any harm?” (pg. 157). This line is twofold valuable: it establishes the demons as a people separate from Ahriman, who despise him and his evil, and also that Rostam is societally “in the wrong” to allow Rakhsh to trample and eat a stranger’s wheat field. This makes Rostam’s later capturing of Olad an even more morally ambivalent act; Olad, already the aggrieved party by Rakhsh’s trespassing, is also attacked on his own land. Yes, Olad is a Div— but he is also a humble farmer and an intelligent man, and slaying him would be an unjust act. Wisely, Rostam spares Olad (and his servant, although the Div loses an ear), coerces him into helping the campaign to free Kavus, and even promises to make Olad king of Mazandaran.

This act of mercy is a turning point for Rostam. Rakhsh kills a lion; Rostam slays a dragon and a witch without hesitation. But now he is showing mercy to a vulnerable enemy. A younger Rostam once called for the indiscriminate slaughter of defeated Turanians before being chastised by Kay Qobad (pg. 140); he would likely have believed in the razing of Mazandaran and killing of Divs. Through the earlier example of Afrasyab (pg. 125), Ferdowsi teaches us that slaughtering prisoners or individuals incapable of defending themselves (such as farmers) is a dishonorable act, and that young, impulsive Rostam deserved his scolding for suggesting it. Though Olad is of the race of the “enemy”, he is not Rostam’s enemy. Sparing Olad— indeed, working with him and trusting his advice— is a mature decision, converging with Rostam’s transition to manhood. Once again the lesson of this labor was not violence; it was abstaining from violence, and learning that a true warrior can delineate between honorable foes and noncombatants.

Historical artists are divided on Olad; many depict him as a true Div, but others seem eager to humanize him to the audience, painting him as a normal man. Perhaps Olad’s eloquence and innocence was difficult for some artists to conceptualize coming from the evil Div. However, I think Olad’s “otherness” is crucial to the lesson of this labor, and my own interpretation draws direct inspiration from an especially beautiful illustration of Olad as monstrous (Appendix B). Like this reference, I have given Olad both clothes (to establish his civility) and breasts (to highlight his otherness.)

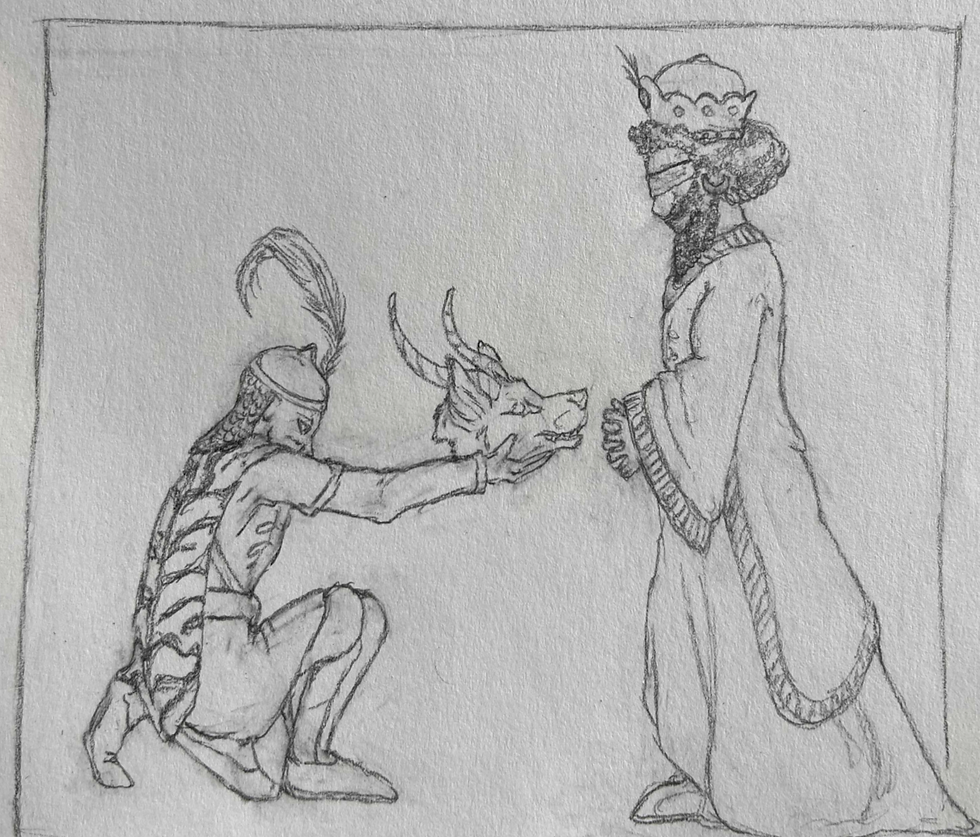

6. Rescuing Kavus - Loyalty to the King

“Sixth Labor – Loyalty”

The subtitle for Rostam’s sixth labor is “Combat with Arzhang”— and artwork depicting this trial almost exclusively shows the moment Rostam tears the Div’s head off— but Arzhang is actually not the focus for most of this section. Rostam decapitates his foe in a single sentence, and lays waste to the rest of the demon army by the end of the paragraph (pg. 160). The rest of this labor is dedicated to Rostam reuniting with Kavus and the captured Persians. Kavus is understandably relieved by the arrival of Rostam, and tells the hero he requires the viscera of the White Demon to cure his blindness. Rostam, of course, is eager to serve his king and country, and rides off on Rakhsh with his reluctant guide Olad in tow. This relationship between Kavus and Rostam— the helpless, sometimes malicious king and his gallant, competent hero— will continue for many years and stories to come. But while Rostam will occasionally come into conflict with Kavus (such as over the treatment of Seyavash (pg. 239)) he will never attempt to depose Kavus or claim the throne for himself. Rostam, like all good men, understands and respects the line between hero and ruler. As his grandfather Sam once explained (pg. 112), the royal bloodline alone is blessed by God with the right to reign.

For this reason, I have chosen to illustrate Rostam presenting the felled Arzhang’s head to Kavus. Rostam is the hero, but Kavus is the king; it is ultimately for Kavus that Rostam slays Arzhang, or undertakes these labors at all. In a sense, his entire transition into manhood is centered around forging this loyalty and bond to the crown that all heroes must have.

7. Slaying Div-e Sepid - The Final Ritual

Rostam’s final trial at last brings him against the champion of the Div, the White Demon. Rostam must prove himself the better warrior and hero (just as the Iranians are proving themselves stronger than the Div) through single combat; his prize is the White Demon’s organs, which he needs to cure Kavus’ of his blindness. His triumph in their duel effectively brings an end to the reigning regime in Mazandaran, allowing the Iranians to install Olad as the new Div king and claim victory over their ancient enemy.

Scholar Mahmoud Omidsalar has written thoroughly about the Oedpedial themes of this battle; the White Demon shares many characteristics with Rostam’s father, Zal, whom Rostam is “deposing” as the new hero of Iran. Building on Omidsalar’s work, I believe there is also a sexual dimension to this battle. Sexual prowess and maturity (another trait of stallions) divides “boys” from “men” almost ubiquitously across cultures. Rostam must therefore transform from a child whose “breath still smells of mother’s milk” to a marriageable man. There are few explicitly sexual encounters in the Shahnameh (although Rostam will have one later in life!), but two erotic elements exist in this labor: penetration with a blade, and dismemberment (tied heavily to castration, consider the example of Zeus and Kronos) of an enemy. Through the slaying of the White Demon, Rostam is both replacing Zal and proving his own sexual capability.

For this artwork, I have depicted Rostam and the Div intertwined in an almost erotic pose. The violence of the act cannot be denied, however, as Rostam plunges his sword through the White Demon’s throat and severs his legs. In reference to the undertones of deposing his own father (as well as finally vanquishing a worthy opponent, the hero of Mazandaran), Rostam wears the hood of his tiger skin cloak against the tiger-headed Div, the two mirroring one another. Many historical paintings of the White Demon give him black spots; I traded this pattern for stripes to further his visual similarity to Rostam. I also drew inspiration from the tradition of “cutaways” to show the inside of enclosed spaces; here, the cave in which Rostam and the Div duel encompasses them all around like a womb.

Upon leaving this dark cave at the end of his last labor, Rostam will be reborn.

Appendix

A. Rahmanian, Hamid. The Second Trial: Rostam in the Desert from Shahnameh: The Epic of the Persian Kings. 2015, digital print on metallic paper, Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont.

B. Unable to find citation; internal illumination

C. There are too many beautiful examples to include them all; here are three

An illumination from a manuscript in possession of The British Library. More information here.

Attributed to Mir Musavvir. Rustam Lassos Rakhsh. Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, ca. 1525 Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper. Smithonsian, Washington D.C.

Cover art for “Magic Stories of Rostam (Tales of Rostam Book 1)” by Sam Zohrehvandi